Brenda Ingram, EdD, LCSW, knows that sexual violence is hard to talk about.

Victims of rape and stalking often feel shame and embarrassment. They fear the consequences of speaking out or seeking help, not knowing if they’ll be taken seriously or have to confront a perpetrator.

In generations past, many college campuses didn’t have the culture or the resources to support students who experience sexual trauma. Now, there is a national push to provide students with more resources such as counseling, support groups and legal advocacy. And universities are moving to train staff and faculty to be approachable in sensitive scenarios.

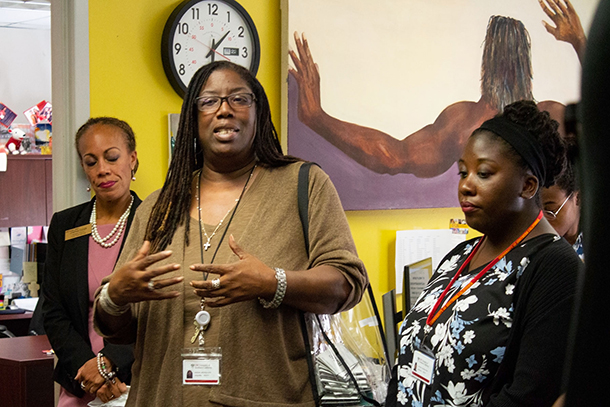

Ingram joined the USC as assistant professor of clinical psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in July to oversee Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention and Services at USC Student Health, and she wants to be part of a cultural sea change related to sexual violence.

Sexual violence prevention at USC: A critical juncture

She has come at a critical juncture.

The day after she accepted the position, allegations about the practices of a former gynecologist at the student health center surfaced. They called to see if she still wanted the job.

She did.

Ingram, who has spent 30 years in education and supporting survivors, sees the timing as a call to action.

“Sexual trauma is the most impactful trauma someone can have,” she said, noting that it brings a high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder. “I really made it my life’s work to tell these stories and help people see it a little differently.”

The national conversation around sexual violence and harassment against women, spurred in part by the #MeToo movement, has shown the enormity of the problem. But college-age women — those ages 18 to 24 — are particularly at risk. Compared to women in general, they’re four times as likely to be sexually assaulted, according to RAINN, the nation’s largest anti-sexual abuse nonprofit.

About 1 out of 3 undergraduate women have reported a sexual assault or sexual misconduct in their time at USC, according to a 2015 survey by the Association of American Universities. It’s a national challenge at universities: 23 percent of female students in the overall survey reported experiencing sexual assault or sexual misconduct. (A new survey will take place this spring at 33 U.S. universities, including USC.)

Sexual violence prevention: at USC and elsewhere, a challenge

The figures are sobering and USC leaders, along with those at many other universities, acknowledge a need to help those students. The survey showed eight out of 10 Trojans turned to friends. Only about 23 percent contacted a university program. About 60 percent contacted DPS, however. Those numbers aren’t surprising, Ingram said.

“Most people don’t seek our services when they are harmed — that’s true for college campuses or off campus,” she said. Instead, they usually confide in a friend or a family member.

Nationally, only about 20 percent of female college students report, according to RAINN. And all data has to take into account underreporting, which is common with sexual violence. The nonprofit reports only two out of three sexual assaults is reported to authorities. The main reasons USC students cited for not reporting were “I did not think it was serious enough to report,” “I did not think anything would be done” and “I did not know where to go or who to tell.”

Ingram wants USC students to know they’re in a supportive environment and that they’re aware of available resources on sexual violence prevention at USC. Her office specifically focuses on sexual violence and relationship violence, offering services such as counseling, advocacy, outreach and crisis intervention.

She also wants to train staff, faculty and administrators to be sensitive to the experiences of students, including those who may be survivors of trauma.

That means training staff and faculty, whether in lectures or small workshops, to make sure that those who work closely with students recognize these students’ needs. It also means advocating for these young people — to help change their schedule or move a test date, if they are struggling.

Recently, a cross-divisional campus group working on consent and healthy relationships created a resource sheet for faculty and staff on how to have compassionate conversations about sexual misconduct.

New resources for sexual violence prevention at USC

In addition, USC Student Health has added 10 therapists this year and added a new position, prevention specialist, solely aimed at sexual violence education.

Ingram, a feminist and leader in the rape crisis movement, is bringing a wealth of knowledge to her position. She became interested in the field while interning for the Berkeley Police Department and the Sacramento County Jail, where she noticed that most of the incarcerated women had been victims of childhood sexual abuse.

She has a Master of Social Work degree and a doctorate in higher education and has taught at UCLA and Pacific Oaks College in Pasadena. She came to USC from Peace Over Violence, a rape crisis center for the state that provides prevention, counseling, case management and legal advocacy. She also has trained Title IX investigators and has hosted trauma workshops at colleges such as Chapman University in Orange.

She is putting energy into expanding outreach and education, through programs such as VOICE (Violence Outreach Intervention and Community Empowerment), a peer outreach program that trains students to support another student in crisis. Last year, only three students showed up to be trained on sexual violence, trauma, stalking and relationship abuse for VOICE, but this fall, Ingram has already interviewed 10 students and asked them to bring along two friends each to the upcoming training. Even though that’s a small group, it’s a 300 percent increase, she said. It’s a beginning.

“Their job is to go out into the campus community to have conversations on both an informal and formal basis,” she said.

“But more importantly I want to encourage them to have one-on-one conversations with their friends, their family, other students — because people are going to learn this through a relationship rather than a presentation where their eyes will glaze over.”

She knows the changes she wants to see won’t happen overnight. But there are reasons for optimism — the campus is starting to talk about these issues, a step toward a culture of openness and empathy.

— Joanna Clay