Kaushik Parvathaneni figured out early on he wanted to work in medicine.

As a teen in high school in Seattle, he reached out to University of Washington faculty, asking if he could help with cancer research. He ended up studying a rare form of skin cancer, Merkel-cell carcinoma.

The lab was experimenting with a new treatment, one-time radiation, to combat an adverse reaction to cancer cells.

“With this Merkel-cell carcinoma, some patients were getting dangerously low sodium levels,” he said.

Parvathaneni, who tracked patients in a database, caught the research bug.

“I was fascinated by the process: Careful methodology and collaborative teamwork generated an answer to a question that had never been answered before. Science truly bridges the gap between the known and the unknown,” he said. “You could say I was hooked.”

Undergraduate research at USC: Opportunity knocks

Then, when he was applying to college, the opportunities to do undergraduate research at USC jumped out at him, like being a faculty member’s research assistant or spending a summer investigating medical questions.

Parvathaneni, a Mork Family Scholar studying human biology, hit the ground running when he got on campus, reaching out to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. There he worked in critical care and pulmonology, focusing on acute respiratory distress syndrome, also known as ARDS.

“It’s sort of like pneumonia but really rare so kids have to be in the intensive care unit for management,” he said.

There was consensus in the medical field that the diagnostic criteria for kids needed to change, but there wasn’t a standardized protocol in place.

“The problem is one we see a lot of times in pediatric medicine — that the definition (of ARDS) was designed for adults,” the 22-year-old said, noting kids are physiologically different than adults. His team applied what they knew about the new pediatric definition to their patients.

It ended up doubling the incidence rate at the hospital, meaning kids were underdiagnosed. He was the lead author on the study, which was published in 2016.

“That was really cool,” he said of the impact. “More kids with ARDS will now get appropriate treatment because previously they wouldn’t have qualified for ARDS.”

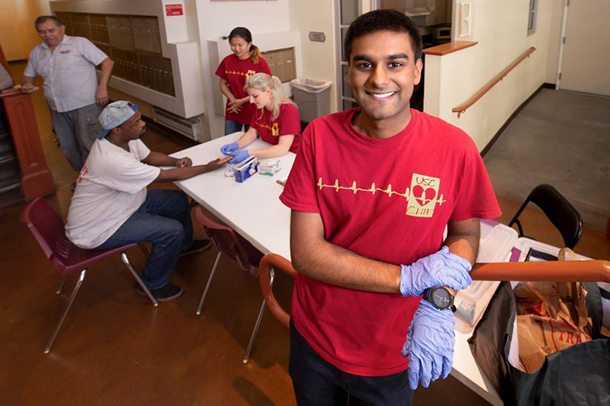

Even though he doesn’t have an MD after his name, he’s found a way to work one on one with patients, too. He volunteers with USC Community Health Involvement Project (CHIP), going to under-resourced communities in L.A. — such as Koreatown, Westlake or down the street in South L.A. — testing people’s blood pressure for hypertension.

“It’s important because a lot of these communities are plagued by diseases like diabetes and hypertension,” he said. “The best way to treat disease is to prevent it in the first place. If we are able to tell people when they’re prediabetes or prehypertension, we can make recommendations like change your diet or do some exercise and change their disease state.”

Caring for communities

During an alternative spring break in rural Nicaragua, he also saw the impact of poverty on healthcare first hand.

“We care for these communities … to create a more equitable society,” he said. “They often face different challenges, i.e. food deserts in South Central L.A. or waterborne pathogens in rural Nicaragua, and it’s important to be cognizant when providing clinical counselling.”

Reaching underserved communities is something he wants to continue during medical school, perhaps working with low-income folks within the transgender community, he said.

“I think they are deserving of a lot of attention,” he said.

Parvathaneni will begin working on his medical degree and a master’s in clinical investigation at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in the fall, coupling his love of clinical work and research.

“I want to be a physician and clinician and work with patients, but I think one of the hallmarks of medicine is that it’s characterized by change,” he said, whether that’s developing new drugs or protocols. “It’s never a static field. It’s dynamic and that’s one of the coolest parts of the profession.”

— Joanna Clay