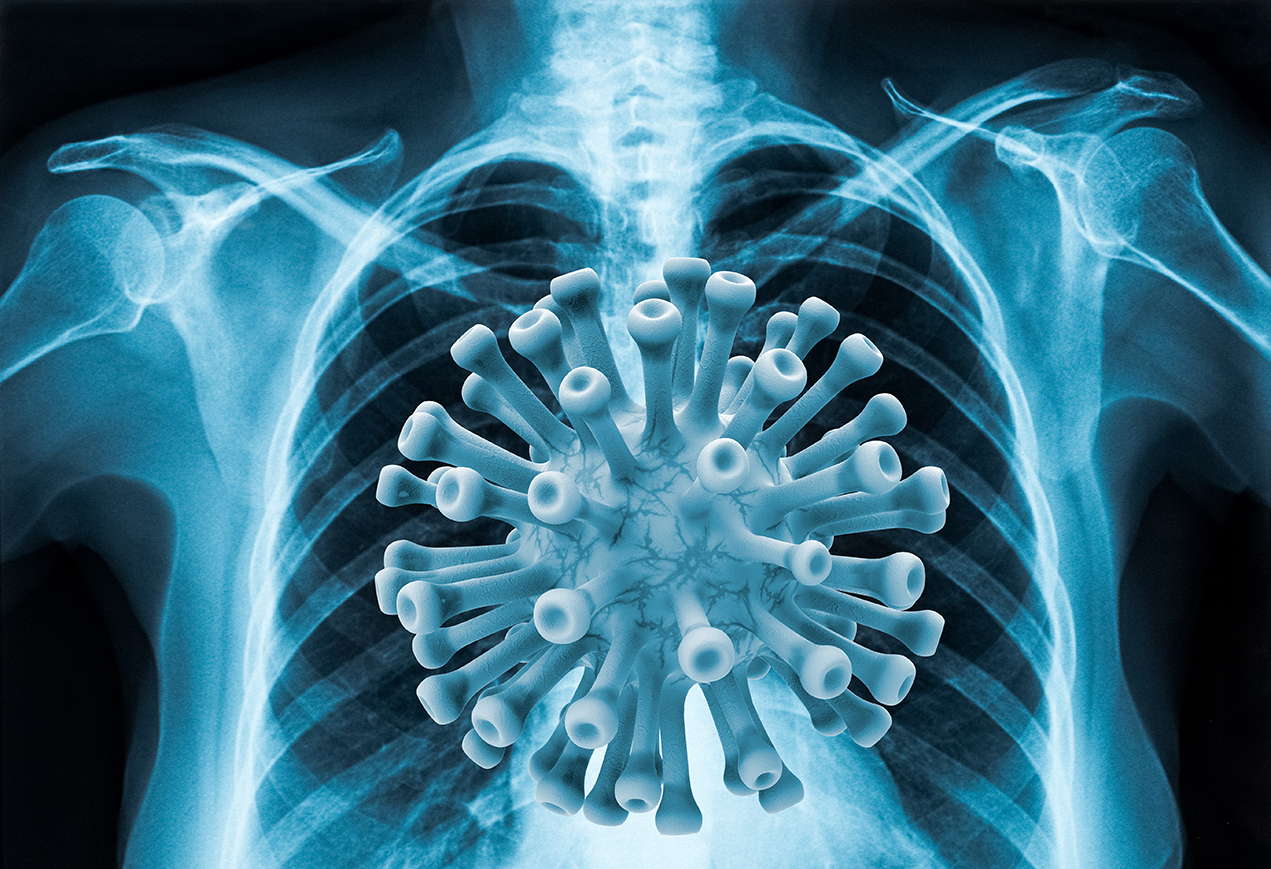

In the early days of the pandemic, before nasal or throat swabs existed to test for COVID-19, health care professionals were dependent on chest imaging to diagnose the disease. Radiologists had front row seats to the novel coronavirus from the start, and they continue to witness its effects on the body.

Ali Gholamrezanezhad, MD, a clinical emergency radiologist with Keck Medicine of USC, was one of the first researchers to study COVID-19 in early 2020. Today, Gholamrezanezhad has co-authored more than 40 papers on the disease, gathering and analyzing a wide array of data and patient scans. He offers his unique insights into a virus that has infected more than 43 million people worldwide.

Patients with COVID-19 don’t necessarily have expected symptoms

“When we run chest CT scans or X-rays on patients with COVID-19, we typically see scattered patchy areas of inflammation in the lungs, which we call atypical pneumonia. These patients usually suffer from a cough, difficulty breathing or chest pain, fatigue and fever.

“What we have found very surprising is that some patients with COVID-19 have no such symptoms. Instead, they present with abdominal pain, or even other symptoms, such as a stroke or an eye inflammation. Yet when we image their lungs, we find COVID-19. On the flip side, much less frequently, patients come in with a cough and fever, and chest imaging reveals that the lungs are clear or have minimal signs of inflammation.

“This may have to do with the fact that COVID-19 affects almost every organ in the body, not just the lungs as was originally thought when the pandemic first began.”

The lung damage caused may be long-term

“My colleagues and I conducted a systematic review of the available published literature on COVID-19 and discovered that up to 30% of patients hospitalized for the coronavirus have lung scarring months after their diagnosis. For patients with mild cases of COVID-19, including those who do not need to be hospitalized, the risk of scarring is generally low. However, for serious cases or people with pre-existing conditions, the risk is high.

“When a lung becomes scarred, the tissue thickens, and the lung works less efficiently. Scarring over 5% of the lung or less isn’t noticeable to most people, because we all have a lot of residual capacity in our lungs. However, if the scarring covers a larger area, patients may have difficulty breathing when they exercise or when they come down with a respiratory infection in the future.

“We don’t yet know if lung scarring due to COVID-19 will disappear over time. However, a study of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which is caused by another type of coronavirus, revealed that patients with SARS still had lung scarring 15 years after contracting the illness.”

Pregnant women may experience a unique complication from COVID-19

“In a systematic review of some 450 CT scans of pregnant women who had contracted COVID-19, we found that 30% had fluid in the pleural cavity that surrounds the lungs, making it harder to breathe. Of the general population with COVID-19, only about 5% show this symptom. This condition probably has to do with the body’s propensity to retain fluid during pregnancy, and is something obstetricians need to be aware of because it can lead to complications during delivery.”

Social distancing is key to prevention

“In another study, my colleagues and I wanted to see the effect that radiology equipment and health care resources played in COVID-19 fatality rates around the world. We investigated more than 20 variables in 40 countries, comparing not only health care-related factors, but issues such as a country’s wealth and education levels and prevalence of obesity, air travel, tobacco use and air pollution.

“We discovered that the biggest factor affecting death rates by far was social distancing. The later a country started the practice of social distancing, the higher the death rate during the first wave of the pandemic. In fact, our model revealed that even a 14-day delay in the implementation of social distancing significantly increased a country’s death rate.”

Don’t assume what we know today will hold true tomorrow

“Every day we are learning something new about COVID-19. What we know about this disease and how we treat it now may be dramatically different in six months to a year. As with all diseases, but never truer than with COVID-19, the learning phase in medicine never ends.”

— Alison Rainey