One of the reasons coronary heart disease is so deadly is that fluid build-up and scarring can develop in the heart tissue. This prevents the heart from contracting properly, impacting its ability to supply the body with fresh blood. If scarring is extensive, heart failure can result.

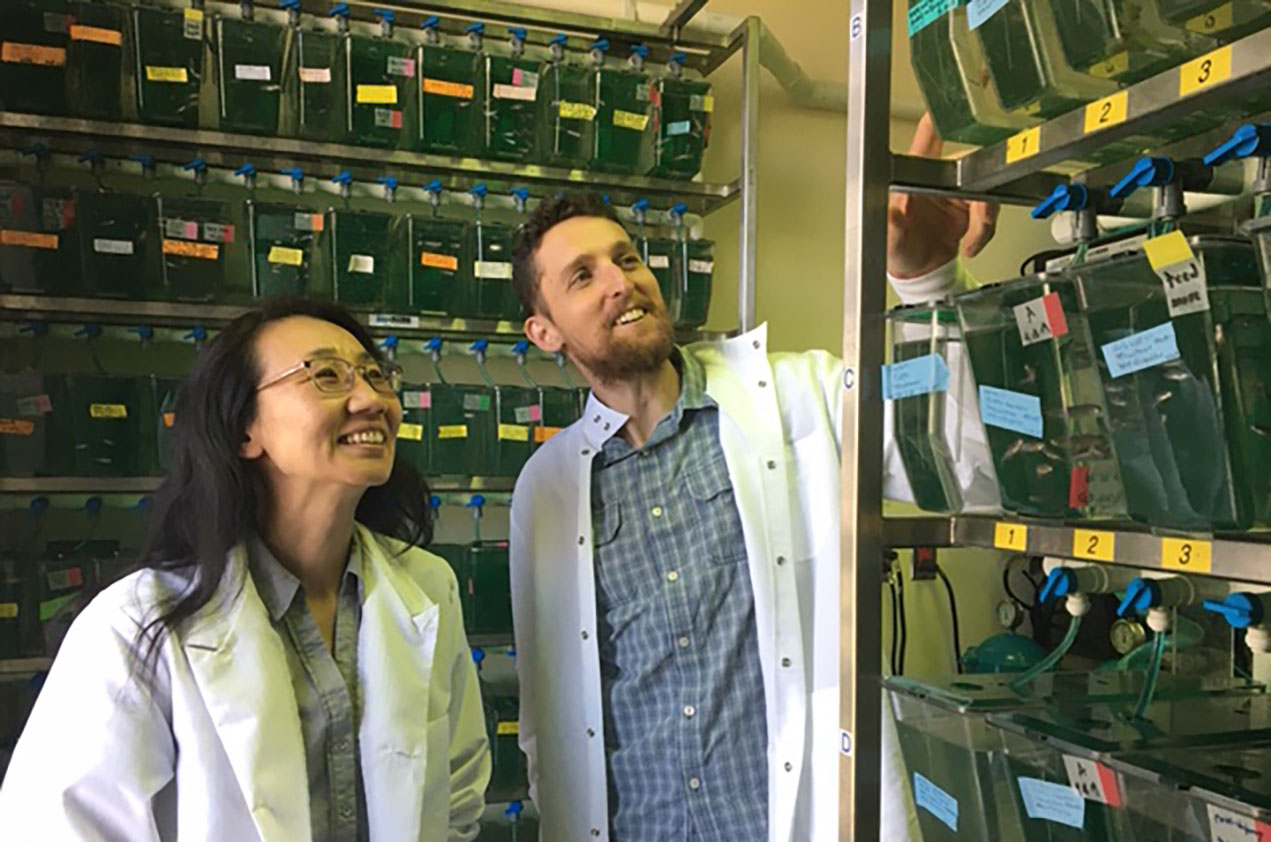

At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles’ Saban Research Institute, Michael Harrison, PhD, a research associate at the institute and Ching-Ling (Ellen) Lien, PhD, assistant professor of surgery at the Keck School of Medicine and principal investigator at the institute, have discovered a mechanism of cardiac regeneration in zebrafish that could change the field of heart research.

“We’re interested in zebrafish because of their incredible capacity for regeneration,” Harrison said. These inch-long creatures are often studied in the field of cardiac repair because they can recover after extensive heart injury.

“Zebrafish can clear the damaged tissue and replace it with fresh, functioning heart muscle,” he said. The question is: How are they able to do this?

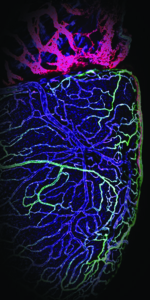

Cardiac lymphatic vessels (red) grow alongside blood vessels (green) in the zebrafish heart.

(Photo/Courtesy Children’s Hospital Los Angeles)

The overall research goal was to uncover the mechanisms used by zebrafish to recover from injury. The answers gained from this research could help develop new treatments for babies with congenital heart defects or individuals who have suffered heart attack or other cardiac injury.

In addition to arteries and veins, many animals — including humans — have a network of lymphatic vessels. This system clears fluid and debris from tissue. Their malfunction may cause fluid build-up or limited clearing of damaged cells after heart injury in humans.

“We don’t see that occurring in the zebrafish,” Harrison said, “so we began to investigate the cardiac lymphatic system in our laboratory.”

Lymphatic vessels are clear, unlike their larger and more colorful blood vessel counterparts. In addition to being hard to see literally, they have also flown under the radar in cardiac regeneration research. In fact, it was not known whether zebrafish even have cardiac lymphatic vessels. Harrison and Lien determined that zebrafish do have these vessels and that they could be a critical factor in heart repair. These findings suggest that the cardiac lymphatic system could be an important research focus in the field of cardiac repair.

In zebrafish with heart damage, the team made a striking observation — the cardiac lymphatic vessels grew and expanded to cover the wound area. When the investigators blocked this process, the fish were unable to repair their heart damage.

“These experiments showed that the lymphatic vessels in the zebrafish heart are doing something critical,” Harrison said. “There’s definitely an important role there.”

Characterizing this role will be the subject of ongoing research. Understanding how the lymphatic vessels are aiding in repair could point scientists toward a treatment target.

“We are looking very closely at these vessels,” Lien said. “We think this is perhaps a new frontier in heart regeneration research.”

The study was recently published in the journal eLIFE. Additional authors on the study include Xidi Feng, Guqin Mo, Antonio Aguayo, Jessi Villafuerte, Tyler Yoshida, Caroline Alayne Pearson, and Stefan Schulte-Merker.

— Melinda Smith