Biomedical researchers have increasingly prioritized large-scale health studies of minority populations in recent years, but datasets often remain limited and inconclusive. While Latinos account for nearly one-fifth of the U.S. population, a recent review estimated that only 3 percent of Alzheimer’s disease studies include Latinos in their analyses.

To help change that, the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School of Medicine of USC is teaming up with researchers from the University of North Texas (UNT) Health Science Center and the University of California, San Francisco. The new collaborative project, Health and Aging Brain among Latino Elders (HABLE), is funded by a $12 million grant from the National Institutes of Health and seeks to gain a better understanding of aging and Alzheimer’s among Mexican-Americans.

Arthur Toga

“Most of the archives around the world have insufficient numbers of underrepresented groups,” said Arthur W. Toga, PhD, director of the institute and one of the principal investigators of the study. “It’s important for people of all races and ethnicities to participate in Alzheimer’s clinical trials, because this disease is a problem that affects all of us.”

The five-year study launched in September. Investigators will recruit and test 2,000 volunteers from North Texas — half Mexican-American and half non-Hispanic white — and hope to learn something new about how the debilitating disease affects Latinos differentially.

“This is the first project specifically attempting to understand how different biological causes relate to Alzheimer’s disease across ethnicities,” said Sid O’Bryant, PhD, associate professor of internal medicine at UNT in Fort Worth, Texas, and principal investigator of the study. “By looking at different potential causes related to memory loss, we may be able to target the right pathway, at the right time, with the right intervention.”

The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that Latinos are 1.5 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-Hispanic whites, and with a growing population of elderly Latinos, researchers are eager to better understand this disparity.

O’Bryant’s previous work points to one possible explanation for Mexican-Americans’ increased risk: metabolic risk factors such as obesity and Type 2 diabetes.

“It could be that diabetes and metabolic dysfunction or depression, or a combination of both, are of major importance to memory loss and Alzheimer’s disease among Mexican Americans,” O’Bryant said.

Researchers will perform cognitive tests, blood work, and brain scans on participants twice during the five-year period to monitor changes in health and behavior over time. O’Bryant’s team even purchased a robot to help handle the mass of data they plan to collect: the bot will process 400,000 blood tubes stored in the university’s biorepository.

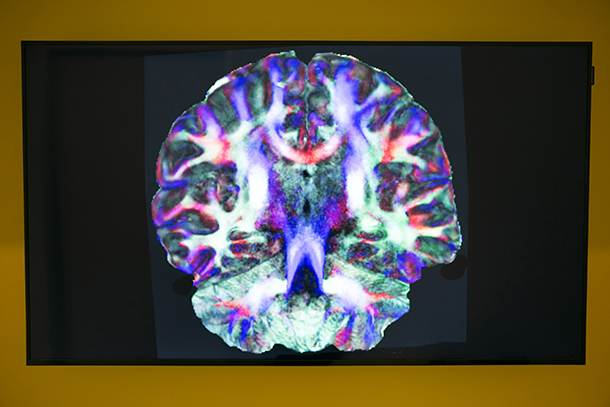

Researchers at the Keck School are responsible for another large chunk of data: 4,000 brain scans. Toga, Provost Professor of Ophthalmology, Neurology, Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, Radiology and Engineering, and the Ghada Irani Chair in Neuroscience, will oversee image storage and processing, while Yonggang Shi, PhD, assistant professor of neurology, and Meredith Braskie, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, respectively will process connectivity and structural images.

Investigators have begun recruiting adults age 50 and older in North Texas, saying that one key to their approach is to study those who do not yet have Alzheimer’s.

“Once people have dementia, their brain has already undergone massive and possibly irreversible damage,” Braskie said. “It’s crucial for scientists to identify very early risk factors and their associated changes in brain measures or cognitive function. This will help us devise treatments that can prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.”

The research is supported by the National Institute on Aging in the Institutes of Health (R01AG054073).

— Zara Abrams