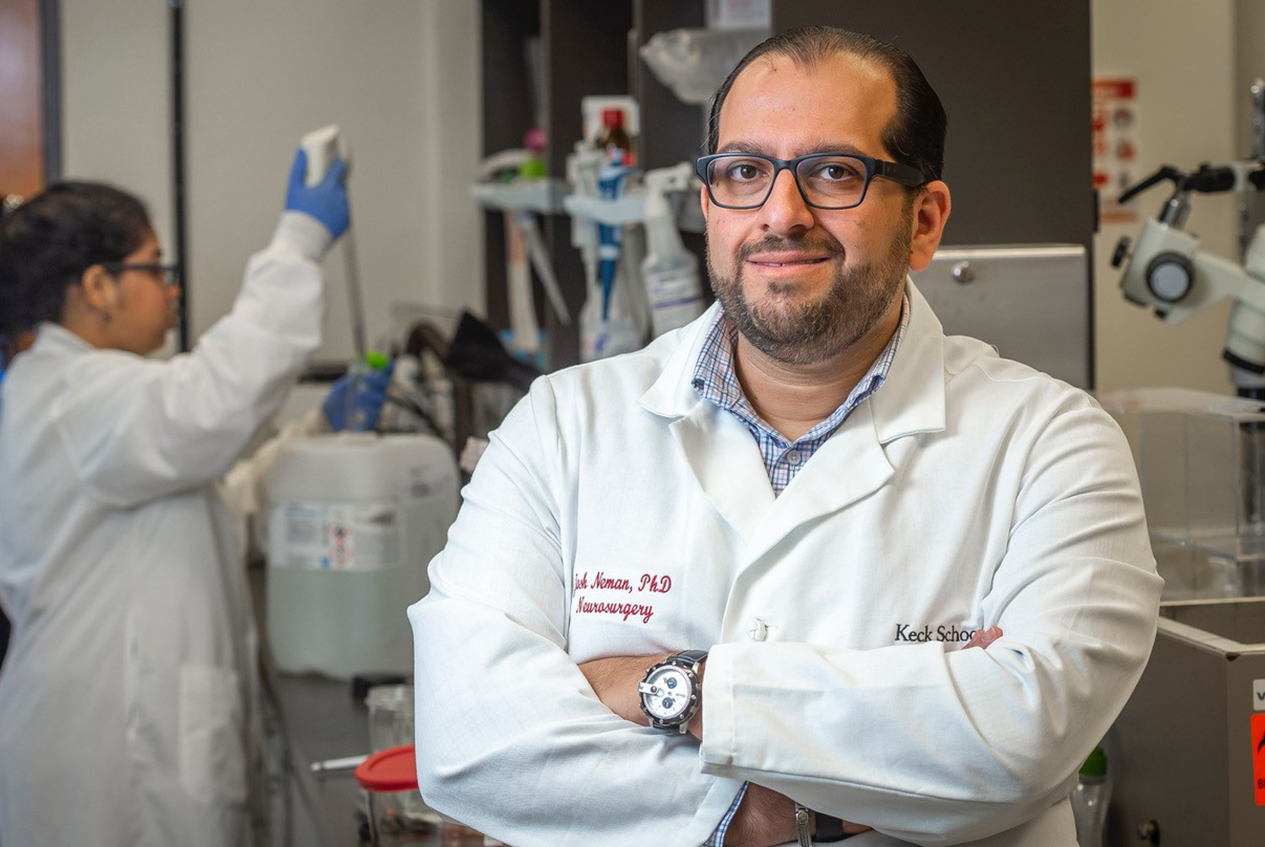

Four years ago, Josh Neman, PhD, scientific director of the USC Brain Tumor Center, gave a talk in Santa Monica for the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation.

There, he met Nohea Avery, the mother of Kalea and Noah. Both Kalea and Noah were diagnosed with medulloblastoma—the deadliest kind of pediatric brain cancer, and the very kind that Neman studies.

Neman had no idea then as he spoke to a room full of concerned parents and caregivers just how significant the Avery family would become to his work.

This past winter, a small but mighty charitable organization in Southern California called the Uncle Kory Foundation announced that Neman had won its first FLAG award—its Fight Like the Averys Grant, named for that same family he’d met—to support his research into medulloblastoma.

The $50,000 merit award came as a surprise to Neman because he and his colleagues had applied for one of the organization’s seed grants, not knowing the FLAG award was just being established.

“It’s bittersweet to receive this grant,” Neman said. “I’m so happy to get the award to do the work, but sad that it’s under such unfortunate circumstances.”

The ravages of medulloblastoma are devastating; the five-year survival rate is low, and for those pediatric patients who do make it, the chemotherapy and radiation used on their developing brains typically does permanent damage.

Unfortunately, both Kalea and Noah succumbed to the cancer, though they—and their parents—fought hard for years.

Stand-out research on pediatric brain tumors

The Uncle Kory Foundation’s scientific advisory board independently reviews all grants and, based on scientific and clinical potential, funds meritorious and promising projects.

“We’re a small organization,” said Renee Vachon, director of operations at Uncle Kory. “So that means we must be very disciplined and thoughtful about the programs we support. We think funding innovative early research, which can lead to much larger awards, is the best way for us to make a difference.”

When Nohea Avery then reviewed the list of funded grants, she chose Neman to be the recipient of the first FLAG award.

“Josh’s research really intrigued her,” Vachon said. “She is very passionate about funding research that will lead to better, safer treatments, specifically designed for children.”

Neman understands the urgency to find novel, more precise treatments to battle medulloblastoma, both to improve the survival rate as well as to protect young brain tissue.

To get there, he studies tumors’ microenvironment in the brain and how the very nature of the brain can sometimes encourage and promote tumors to spread.

“We’re finding out the normal and healthy cells of the body actually contribute a lot to tumor growth,” he said. “Cancer cells hijack the body and appear as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, asking other cells to help them out.”

In the case of medulloblastoma, rogue cancer cells left over after surgical resection of the tumor develop resistance to radiation and chemotherapy and become even more aggressive in their growth.

They trick one of the brain’s main chemical neurotransmitters and use that as fuel to then spread down the spinal cord, where any kind of treatment becomes especially risky.

A strategy for dismantling tumor cells

As smart and tricky as medulloblastoma seems, that particular kind of tumor might have met its match in Neman and the USC Brain Tumor Center team – especially with the FLAG award to back their pilot study.

Neman’s lab figured out which protein and chemical neurotransmitter the cancer manipulates and has identified a new potential inhibitor of that protein called NEO216, developed by Keck Medicine of USC neurosurgeon Thomas Chen, MD, PhD.

Essentially, they hope to use NEO216 to sever the line of communication between the brain and the cancer cells’ protein. No communication equals no hijacking of fuel, and thus, no growth. The rogue tumor cells would die out.

As a bonus, Neman hopes they can also use NEO216 to target and reduce the main tumor, making for a much safer and effective therapy, ultimately decreasing the suffering for pediatric patients on several fronts, increasing survival and preserving their sensitive brains.

The grant will fund the pilot study to first test NEO216 in mice. If the results look as promising as Neman expects, then he and his team will take the next step of going into Phase I of human clinical trials, ultimately seeking FDA approval for this as a new treatment for medulloblastoma.

“Our preliminary data shows that this drug works, and that it really works,” Neman said.

He anticipates a Phase I trial could be as near as three to four years away. “We’ve made significant inroads, but we have to prove it still.”

Neman credits his colleagues at the USC Brain Tumor Center, including then-graduate student Vahan Martirosian, who was integral in the initial studies of the drug and gaining the grant funding.

While he’s clearly passionate about the fight against medulloblastoma, Neman said, “As a cancer researcher, I can’t wait to be out of a job.”

—Janice O’Leary