A new study led by faculty at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and fellows at the USC Schaeffer Center shows mental health-related emergency department (ED) visits have increased substantially since 2009, a trend driven by large increases in adolescent and young adult visits to the emergency room for behavioral health-related diagnoses.

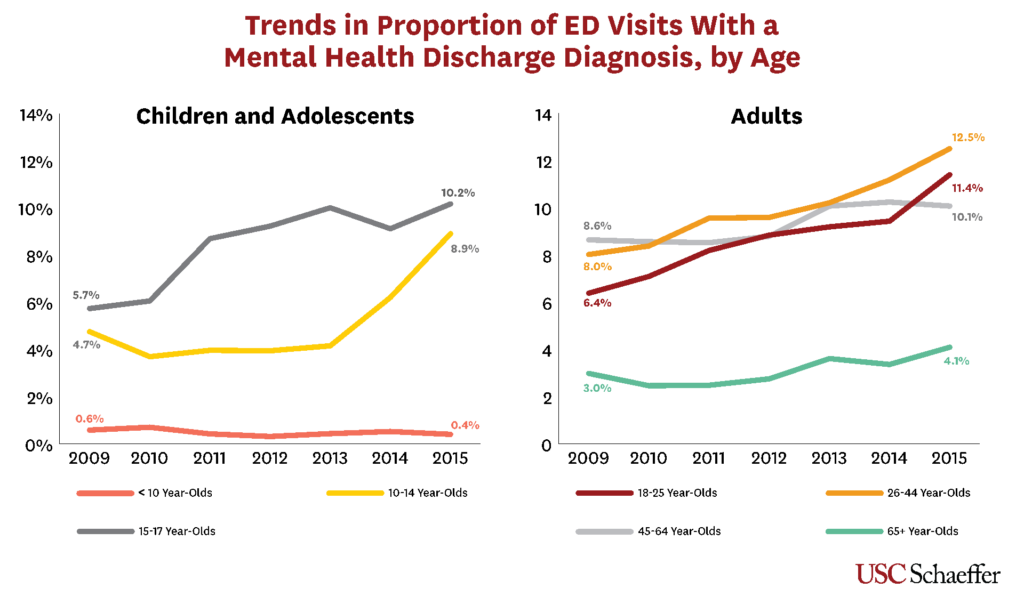

The study showed that for patients between 10 and 25 years old, annual growth rates for behavioral health-related visits were double those of older age groups.

“Given the documented rise in use of the emergency department for mental health complaints, we set out to better understand who these patients are, whether the ED was capable of effectively and efficiently treating these patients, and what policy changes might be necessary to improve care and maintain well-running EDs ,” said Sarah Axeen, PhD, assistant professor of research in the department of emergency medicine at the Keck School and a fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics who served as an author on the study.

Utilization of ED services for mental health-related visits can be challenging for hospitals to manage for a number of reasons. In order to examine the larger picture of ED ability to treat emergent mental-health encounters, Axeen and colleagues at the Keck School evaluated data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS) on ED encounters between 2009 and 2015. Their results were published in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

Overall, mental health-related visits grew by 56 percent for pediatric patients and by almost 41 percent for adults. The authors defined an ED visit as mental health-related when one of the first three ED diagnoses was for a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis.

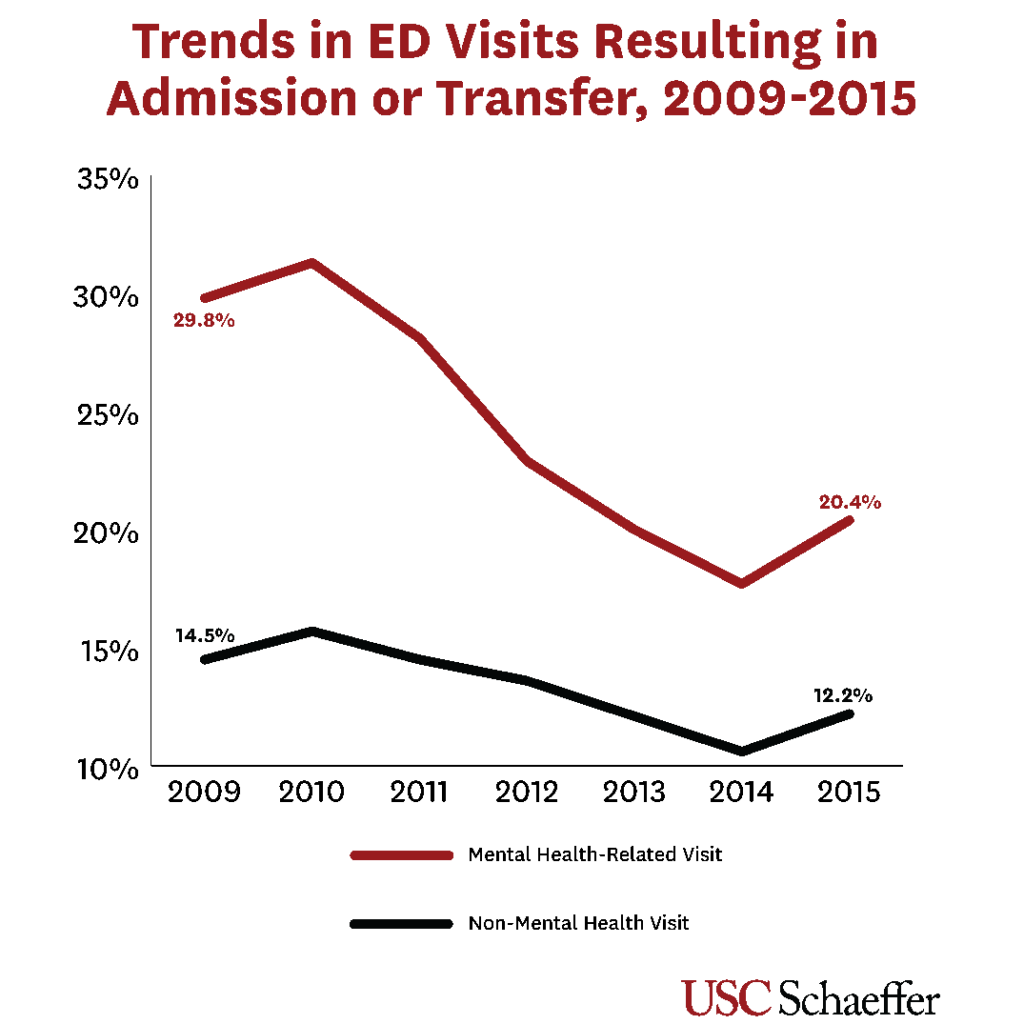

The data showed that not only did the proportion of behavioral health visits increase, the average length of stay for these patients, across all age groups, increased from 6.5 hours in 2009 to 9.0 hours in 2015. This increase was due almost entirely to patients who were admitted or transferred to a psychiatric facility rather than to those discharged home. Patients who were eventually admitted or transferred to a psychiatric facility averaged the longest stays, increasing from 8.0 to 11.4 hours.

“Emergency departments are increasingly serving as a key place to initially treat children and adolescents experiencing mental health or behavioral crises. Unfortunately, we are seeing more and more patients with the most serious crises — those who have to be admitted to the hospital — and these patients are staying longer and longer in the ED,” said study co-author Michael Menchine, MD, associate professor of clinical emergency medicine and vice chair of the emergency department at the Keck School.

He went on to explain, “EDs are almost universally beyond capacity so any trend in patients staying longer is a problem since it impacts our ability to have space and resources to see the next patient. But, more importantly, EDs are just not great therapeutic environments for people having these kinds of crises,” he said. Menchine is also a clinical fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center and works in the emergency department at LAC+USC Medical Center.

These increased lengths of stay are particularly problematic for ED waiting times as the proportion of patients who were admitted or transferred was significantly higher for behavioral health-related visits compared to non-behavioral health related visits.

Adolescents were more likely to be admitted or transferred during behavioral health-related visits compared to any other age group. Nearly a third of mental health-related visits of 15 to 17-year olds — part of the age group largely driving the upward trend of these ED visits — were admitted or transferred, while less than 5 percent of non-mental health-related visits were. Among 10 to 14-year olds, 28.4 percent of mental health-related visits resulted in admission or transfer compared to 4.3 percent of the age group’s non-mental health visits.

“The concentration of mental health visits resulting in admission or transfer among this adolescent population is particularly notable as they may require specific, pediatric psychiatric facilities or beds,” Axeen said. “This specialized need might further exacerbate waiting times and require relatively greater use of ED resources; future research should work to determine the additional impact of these age restrictions on length of stay for adolescent patients.”

Taxing the System

Between 2009 and 2015, 8.2 percent of all ED visits by adults and 2.5 percent of visits by children were mental health-related. However, these visits accounted for 11.2 and 4.9 percent of all ED hours spent with adults and children.

“This disproportionate utilization of ED time likely contributes to overall ED crowding which is, in turn, associated with decreased quality of care for multiple conditions,” the authors wrote. “As such, the increase in mental health-related visits may have negative spillovers onto the care of all ED patients.”

The authors suggest additional funding for training emergency physicians to better care for these patients and additional resources if these trends continue. Policy levers could also include more funding for non-emergent mental health resources in an effort to focus ED care on acute diagnostic issues. Psychiatric observation units and sobering centers, like the Los Angeles Fire Department Sobriety Emergency Response (SOBER) unit can also serve some of the non-emergent behavioral health-related needs, as can expanding tele-psychiatry services and regionalized mental health assistance for adolescents; all require initial funding and maintenance costs.

Looking Ahead

A grant from the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM) Foundation will fund further research by Axeen, Menchine, Seth Seabury, PhD and others at the Keck Schaeffer Initiative for Population Health Policy to understand the capacity of hospitals and their ED to treat behavioral health diagnoses.

“Our results indicate that the ability of the ED to discharge, admit, or transfer patients with mental health diagnoses greatly impacts the care these patients receive in the ED,” said Axeen. “Our goal is to directly estimate which characteristics of ED or hospital capacity account for this variation in order to improve the quality and consistency of emergency mental health care for patients.”

Continued research will provide a more nuanced understanding on how patients who arrive at the ED with mental health or substance abuse complaints are diagnosed, initially treated and whether they receive further support for their behavioral health issues.

Additional study authors include Genevieve Santillanes, MD, a pediatric emergency medicine physician and Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Chun Nok Lam, Project Manager and Senior Analyst at the Department of Emergency Medicine, both at the Keck School.

— Gretchen A. Meier