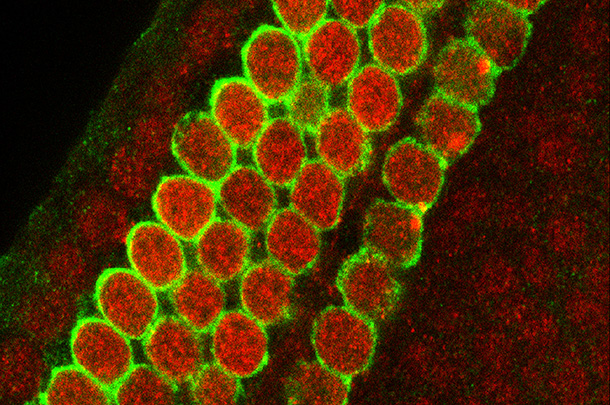

The chemotherapy drug cisplatin can kill cancer, but it can also kill the sensory cells of the inner ear — causing permanent hearing loss. This hearing loss is likely to be more severe in individuals with Cockayne syndrome, according to a new study on the cover of The Journal of Neuroscience.

In the study, USC Stem Cell researchers Robert N. Rainey, PhD, and Sum-yan Ng, PhD, from the laboratory of Neil Segil, PhD, demonstrated that cisplatin causes more acute hearing loss in mice with the equivalent of Cockayne syndrome.

In humans, Cockayne syndrome can cause hearing loss as well as eye abnormalities, shortness, skeletal deformities, microcephaly, nervous system underdevelopment, an appearance of premature aging and sun sensitivity. In another study published in The Journal of Neuroscience last year, the researchers established a new strain of mouse that models Cockyane syndrome-associated hearing loss.

The disorder results from mutations in one of two genes — called Csa and Csb — involved in repairing DNA damage. Cells can sustain DNA damage from environmental stresses ranging from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation to toxic chemicals such as chemotherapy drugs.

Like similar chemotherapy drugs, cisplatin damages the DNA in cells, interfering with their ability to proliferate. This interference is expected to have the most pronounced effect on the most proliferative cells, such as cancer cells, and the least effect on non-dividing cells, such as the sensory cells of the inner ear. However, in practice, cisplatin causes significant death of both quickly dividing cancer cells and the non-dividing sensory cells of the inner ear — making it an effective chemotherapy drug with a common side effect, severe hearing loss. Young children undergoing cisplatin chemotherapy appear to be particularly vulnerable, and consequently experience developmental delays as a result of early hearing loss.

Like humans with Cockayne syndrome, mice with mutations in Csa and Csb can’t efficiently repair DNA damage, leaving them particularly vulnerable to permanent hearing loss from cisplatin. In the study, mice with the Csa mutation fared somewhat worse than mice with the Csb mutation.

Both mutations interfere with what is known as transcription-coupled DNA repair, or TCR. While there are many different ways that cells can repair DNA damage, TCR appears to play a particularly important role in protecting the sensory cells of the inner ear from cisplatin. Variation between individuals in the effectiveness of TCR may help explain the differing susceptibility to hearing loss due to environmental stress and aging.

“Our cells have several biochemical pathways that they use to repair DNA. Our findings suggest that one particular pathway, transcription-coupled DNA repair, is a major force for protecting the cells of the inner ear from cisplatin,” said Segil. “This leaves patients with Cockayne syndrome particularly vulnerable to severe hearing loss as a side effect of taking this chemotherapy drug.”

Additional authors include Juan Llamas from USC and Gijsbertus T.J. van der Horst, PhD, from the Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

Funding came from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F32DC010125) and an NIH grant (R01DC007173), and the Sidgmore Family Foundation.

— Cristy Lytal