The key to a better understanding of schizophrenia may exist in a genetic disorder so rare that researchers haven’t been able to conduct an adequate study — until now.

The genetic disorder 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11DS), caused by a small segment of missing DNA on chromosome 22, is the strongest known genetic risk factor for developing schizophrenia. About a quarter of people with the disorder develop schizophrenia or experience psychotic symptoms, so studying it provides a unique window into how such psychiatric problems develop over time.

But there’s one problem: Only about one in 4,000 people have it. Even a large city like Los Angeles may hold just a few hundred people with the condition.

Fortunately, the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) consortium, led by Paul M. Thompson, PhD, associate director of the Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (INI) at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, has spent the past 10 years uniting researchers around the world to pool data and insights on rare diseases. Now, ENIGMA has launched a new working group to study 22q11DS using data collected by researchers across the U.S., Canada, Europe, Australia and South America.

“We’ve pieced together many of the major research centers studying 22q11DS around the world to create the largest-ever neuroimaging study of the disorder,” said Christopher Ching, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the INI and lead author of the working group’s latest study.

Thompson, Ching and the ENIGMA 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome Working Group published their results in the American Journal of Psychiatry on Feb. 12.

Correlations become clear with advanced neuroimaging

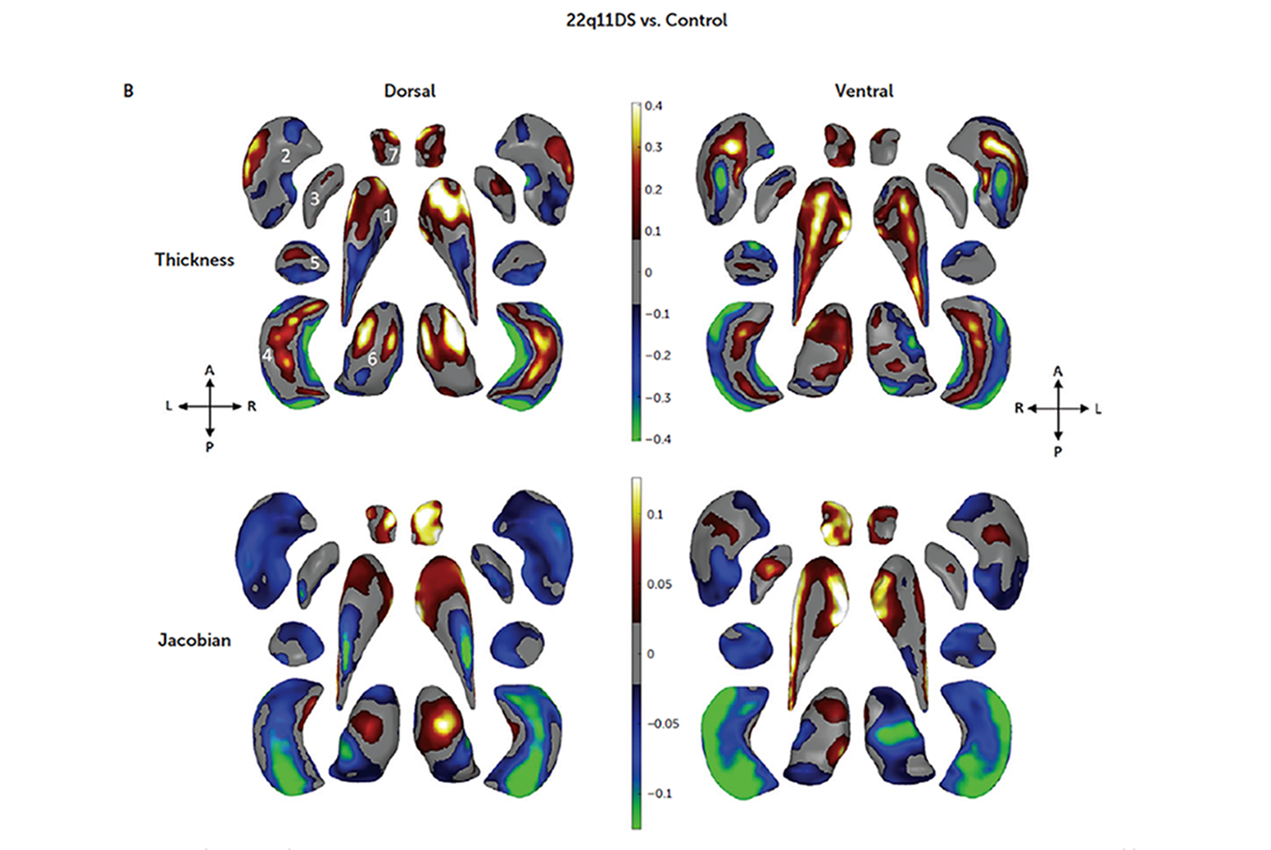

To get a clear picture of the brain abnormalities associated with schizophrenia in individuals with 22q11DS, the study’s authors examined magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 533 people with the disorder and 330 healthy control subjects. Using advanced analytic techniques developed at the USC INI, the authors measured and mapped structural differences between the brains of the two groups.

Overall, individuals with 22q11DS had significantly lower brain volumes, as well as lower volumes in specific structures including the thalamus, hippocampus and amygdala, compared with the control group. They also had higher volumes in several brain structures. The magnitude of these abnormalities, especially in those 22q11DS individuals that had psychosis, was larger than is typical in many other common psychiatric conditions.

Notably, the brain changes seen in people with 22q11DS and psychosis significantly overlapped with the brain changes observed in the largest-ever neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses including bipolar disorder, major depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

“That’s important because these overlapping brain signatures add evidence to support 22q11DS as a good model for understanding schizophrenia in the wider population,” Ching said. “And thanks to these large ENIGMA studies, we now have a way to directly compare standardized brain markers across major psychiatric illnesses on an unprecedented scale.”

This powerful connection means that studying 22q11DS may provide a clear path toward finding a biomarker, or a reliable biological indicator, of schizophrenia. Because of the large sample size used in the analysis, the researchers also found that larger segments of missing DNA in 22q11DS are linked to more extensive brain abnormalities.

Next steps in research

Looking forward, the study’s authors aim to explore the similarities between brain abnormalities in individuals with 22q11DS and those with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, drawing on data from other ENIGMA groups to better understand whether various psychiatric illnesses may share common origins and affect similar or distinct brain circuits.

The group also plans to use these new analytic tools to explore 22q11DS in animal models, where they can conduct more controlled experiments to better understand the effects of the missing DNA segments across development.

“We can even experimentally manipulate specific genes within the locus to better understand how and when they are affecting the development of these brain structures,” said Carrie Bearden, PhD, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral science and psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, chair of the working group and corresponding author of the study.

— Zara Greenbaum

The study was funded by NIH grant U54EB020403 from the Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) Program, NIMH Grant RO1 MH085953, and NIA T32AG058507.