Here’s another reason to start the day with a cup of joe: Scientists have found that people who drink coffee appear to live longer.

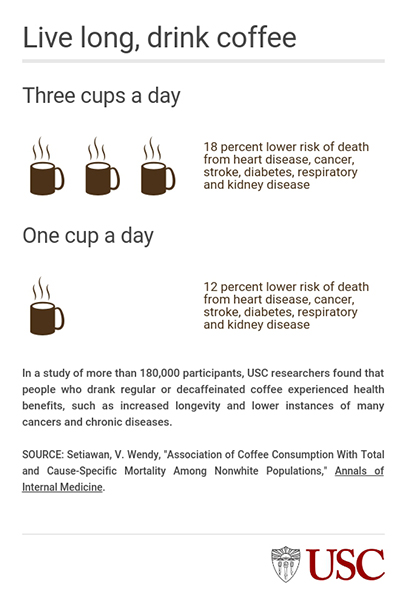

Drinking coffee was associated with a lower risk of death due to heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and respiratory and kidney disease for African-Americans, Japanese-Americans, Latinos and whites.

People who consumed a cup of coffee a day were 12 percent less likely to die during the study period compared to those who didn’t drink coffee. This association was even stronger for those who drank two to three cups a day — 18 percent reduced chance of death over the course of the study.

Lower mortality was present regardless of whether people drank regular or decaffeinated coffee, suggesting the association is not tied to caffeine, said V. Wendy Setiawan, PhD, senior author of the study and an associate professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“We cannot say drinking coffee will prolong your life, but we see an association,” Setiawan said. “If you like to drink coffee, drink up! If you’re not a coffee drinker, then you need to consider if you should start.”

The study, which was published in the July 11 issue of Annals of Internal Medicine, used data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study, a collaborative effort between the University of Hawaii Cancer Center and the Keck School.

The ongoing Multiethnic Cohort Study has more than 215,000 participants and bills itself as the most ethnically diverse study examining lifestyle risk factors that may lead to cancer.

“Until now, few data have been available on the association between coffee consumption and mortality in nonwhites in the United States and elsewhere,” the study stated. “Such investigations are important because lifestyle patterns and disease risks can vary substantially across racial and ethnic backgrounds, and findings in one group may not necessarily apply to others.”

Since the association was seen in four different ethnicities, Setiawan said it is safe to say the results apply to other groups.

“This study is the largest of its kind and includes minorities who have very different lifestyles,” Setiawan said. “Seeing a similar pattern across different populations gives stronger biological backing to the argument that coffee is good for you whether you are white, African-American, Latino or Asian.”

Benefits of drinking coffee

Previous research conducted at USC and other institutions have indicated that drinking coffee is associated with reduced risk of several types of cancer, diabetes, liver disease, Parkinson’s disease, Type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases.

Setiawan, who drinks one to two cups of coffee daily, said any positive effects from drinking coffee are far-reaching because of the number of people who enjoy or rely on the beverage every day.

“Coffee contains a lot of antioxidants and phenolic compounds that play an important role in cancer prevention,” Setiawan said. “Although this study does not show causation or point to what chemicals in coffee may have this ‘elixir effect,’ it is clear that coffee can be incorporated into a healthy diet and lifestyle.”

About 62 percent of Americans drink coffee daily, a 5 percent increase from 2016 numbers, reported the National Coffee Association.

As a research institution, USC has scientists from across disciplines working to find a cure for cancer and better ways for people to manage the disease.

The Keck School and USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center manage a state-mandated database called the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program, which provides scientists with essential statistics on cancer for a diverse population.

Researchers from USC Norris have found that drinking coffee lowers the risk of colorectal cancer.

But drinking piping hot coffee or beverages probably causes cancer in the esophagus, according to a World Health Organization panel of scientists that included Mariana Stern from the Keck School.

Hearing from the WHO

In some respects, coffee is regaining its honor for wellness benefits. After 25 years of labeling coffee a carcinogen linked to bladder cancer, the World Health Organization last year announced that drinking coffee reduces the risk for liver and uterine cancer.

“Some people worry drinking coffee can be bad for you because it might increase the risk of heart disease, stunt growth or lead to stomach ulcers and heartburn,” Setiawan said. “But research on coffee have mostly shown no harm to people’s health.”

Coffee by the numbers

Setiawan and her colleagues examined the data of 185,855 African-Americans (17 percent), Native Hawaiians (7 percent), Japanese-Americans (29 percent), Latinos (22 percent) and whites (25 percent) ages 45 to 75 at recruitment. Participants answered questionnaires about diet, lifestyle, and family and personal medical history.

They reported their coffee drinking habits when they entered the study and updated them about every five years, checking one of nine boxes that ranged from “never or hardly ever” to “4 or more cups daily.” They also reported whether they drank caffeinated or decaffeinated coffee. The average follow-up period was 16 years.

Sixteen percent of participants reported that they did not drink coffee, 31 percent drank one cup per day, 25 percent drank two to three cups per day and 7 percent drank four or more cups per day. The remaining 21 percent had irregular coffee consumption habits.

Over the course of the study, 58,397 participants — about 31 percent — died. Cardiovascular disease (36 percent) and cancer (31 percent) were the leading killers.

The data was adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking habits, education, preexisting disease, vigorous physical exercise and alcohol consumption.

Setiawan’s previous research found that coffee reduces the risk of liver cancer and chronic liver disease. She is currently examining how coffee is associated with the risk of developing specific cancers.

Researchers from the University of Hawaii Cancer Center and the National Cancer Institute contributed to this study. The study used data from the Multiethnic Cohort Study, which is supported by a $19,008,359 grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

— Zen Vuong