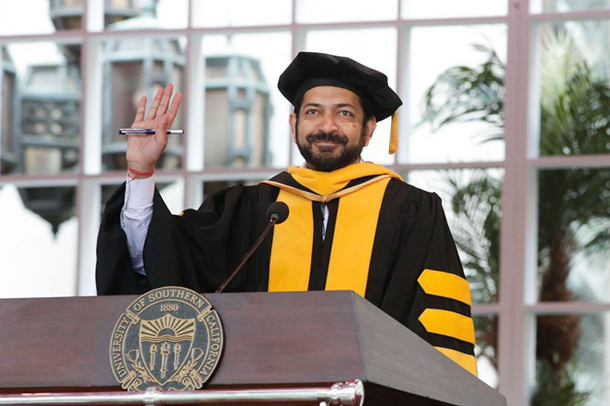

When Siddhartha Mukherjee took the stage at the USC 2018 commencement this morning, he shared a tip with a new generation of Trojans.

“I wish someone had told me at my own commencement that the one and only requirement of graduation was not that I finish these many credits, or pull those many all-nighters, or attend these many late-night mixers or, for that matter, survive Drew Casper’s lectures,” said Mukherjee, the Pulitzer-Prize winning author of the 2011 book The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer and renowned oncologist.

The sole requirement, he said: listening. That can mean exploring the inner workings of the universe, empathizing with a frustrated patient or understanding the logic of a virus’s attack on the body, he said.

USC 2018 commencement: More than 17,000 graduates

It was a message he shared with a crowd of roughly 60,000, who were cheering on 17,823 new graduates representing more than 100 countries.

While their academic journey may be coming to an end, a new adventure awaits them, USC President C. L. Max Nikias said.

“Trojans are forever discovering new worlds and reimagining old ones,” Nikias said. “But remember: You do not go forward alone. You go forward as treasured members of the Trojan Family, a family that forever connects you to this campus, and to each other, across the decades of your lives and the continents of our world.”

Valedictorian Rose Campion found inspiration for their futures by looking to the past. She recalled the 1918 USC commencement, which graduated 620 students with 100 missing — off fighting for the Allies in World War I.

Students that day were told to go “continue the world’s reconstruction.” Campion, who majored in history and music, hopes Trojans can continue that fight to restore peace around the world. Like Mukherjee, she mentioned listening as a way to do it.

“Find a way to continue practicing empathy each and every day after we leave this campus,” she said. “Fight our prejudices, fight those trends that divide us and, of course, always fight on.”

A lesson in listening

Mukherjee remembered a lesson he learned. It was during the first year of his residency, when he was caring for a man with esophageal cancer — a plumber named Steve in his late 30s about to get his ninth round of chemotherapy.

“He came to the hospital and said flatly, ‘I don’t want to fight this war,’ ” he said. “I am not a soldier. I want a cookie.”

Mukherjee could have pushed him but instead, he told him to go home and got him a cookie.

“Chemo could wait. … The tests could wait. I could wait,” he said to Steve, asking him to return in a week.

Steve ended up living another two years and see his oldest son graduate from high school, thanks to intensive treatment.

“If I had pushed him too hard that morning, I would have lost him as a patient,” he said.

Mukherjee urged students to continue carrying listening as a tool in their arsenal.

“You are part of the new order. You will hear each other out,” he said of the “listening generation.” “Your predecessors tried, but … we could not get out of our own heads.

“Unlike us, you will really, really defend the defenseless,” he said. Learn from history, he added, and discover the laws of nature that others missed.

“Go get out of your heads, go out in the world and listen to it — and most importantly, please, make us listen to you,” he said.

Mukherjee, whose book was adapted into a Ken Burns PBS documentary, was one of five presented with honorary degrees. Other recipients were Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck, Academy Award-winning actor Forest Whitaker, biochemist Jennifer A. Doudna and former NASA Administrator Maj. Gen. Charles F. Bolden Jr.

— Joanna Clay