A 20-year study by Keck Medicine of USC scientists has found that millennial children in Southern California breathe easier than ones who came of age in the `90s.

The gains in lung function paralleled improving air quality in the communities studied — and across the L.A. basin — as policies to fight pollution have taken hold.

The research appeared in the March 5 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many studies have measured the health effects of pollution by comparing locations with different air quality. The challenge lies in ruling out other factors that may account for health differences between communities.

By following more than 2,000 children in the same locations over two decades and adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, height, respiratory illness and other variations, the study provides stronger evidence that improved air quality by itself brings health benefits — benefits that last a lifetime for children breathing cleaner air during their critical growing years.

“We saw pretty substantial improvements in lung function development in our most recent cohort of children,” said lead author W. James Gauderman, PhD, professor of preventive medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

He noted that this is the first good news from the long-running study. “It’s strange to be reporting positive numbers instead of negative numbers after 20 years.”

Previous findings from the study that showed an increase in stunted lung development for children in areas with heavy air pollution were widely reported, as was a higher risk of asthma for children living near busy roadways.

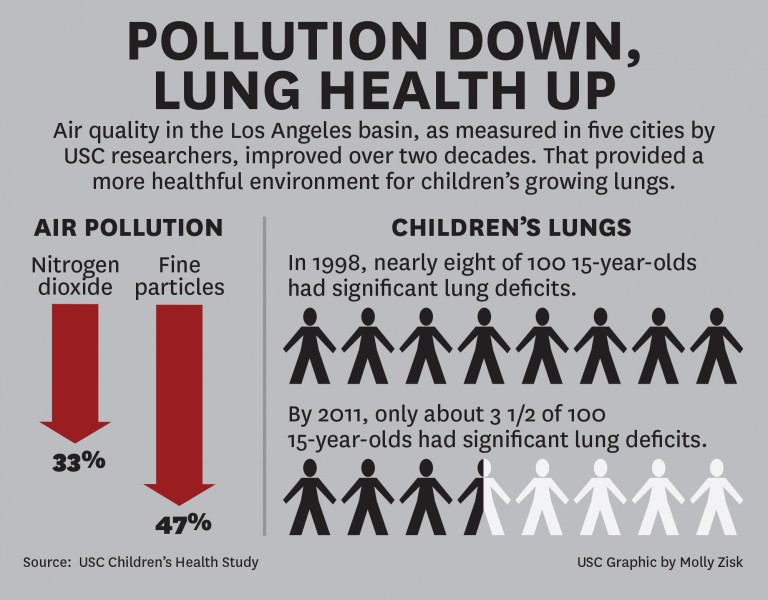

Combined exposure to two harmful pollutants, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter of diameter under 2.5 microns (PM2.5), fell by approximately 40 percent for the group designated as the third cohort of 2007-2011 as compared to the first cohort of 1994-98. The study followed children from Long Beach, Mira Loma, Riverside, San Dimas and Upland.

Children’s lungs grew faster as air quality improved. Lung growth from ages 11 to 15 was more than 10 percent greater for children breathing the lower levels of NO2 from 2007 to 2011 compared to those breathing higher levels from 1994-1998.

The percentage of children in the study with abnormally low lung function at age 15 dropped from nearly 8 percent for the 1994-98 cohort to 6.3 percent in 1997-2001 to just 3.6 percent for children followed from 2007 to 2011.

That compares to 2.5 percent by age 18 for children from the first two cohorts who lived in cities with cleaner air, such as Lompoc and Santa Maria. Cuts in federal funding forced the researchers to exclude those cities in the last cohort and focus only on areas with heavier air pollution.

“Reduced lung function in adulthood has been strongly associated with increased risks of respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease and premature death,” Gauderman said. “Improved air quality over the past 20 years has helped reduce the gap in lung health for kids inside, versus outside, the L.A. basin.”

The growing years are critical for lung development. The researchers are monitoring lung function in a group of adults who participated in the study as adolescents. So far they have not found evidence of a rebound after the teenage years.

“Their lungs may have lost the opportunity to grow any more,” Gauderman suggested.

Lung development measured by the study improved across the board, regardless of education, ethnicity, tobacco exposure, pet ownership and other factors.

Lung development measured by the study improved across the board, regardless of education, ethnicity, tobacco exposure, pet ownership and other factors.

Across all five communities, lung development for children with asthma improved roughly twice as much as for other children. But even children without asthma showed significant improvements in their lung capacity, suggesting that all kids benefit from improved air quality.

“We expect that our results are relevant for areas outside Southern California, since the pollutants we found most strongly linked to improved health — nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter — are elevated in any urban environment,” Gauderman said.

The incidence of asthma did not change significantly over the three cohorts. Previous research by the Children’s Health Study showed that the risk of asthma increases with proximity to busy roadways.

Local, state and federal regulations have achieved large reductions in pollutants in the Los Angeles basin.

Visibility also has improved. Southern California locations surpassed their 2018 state goals by 2012.

“It’s an environmental success story. The air has gotten much cleaner than it was in the past. I grew up here in the `70s. Even from Pasadena you couldn’t see the San Gabriel Mountains on a typical summer day,” Gauderman said.

Gauderman cautioned: “We can’t get complacent, because not surprisingly the number of vehicles on our roads is continually increasing. Also, the activities at the ports of L.A. and Long Beach, which are our biggest polluting sources, are projected to increase. That means more trucks on the road, more trains carrying cargo.”

“These gains really aren’t fixed,” added senior author Frank Gilliland, MD, MPH, PhD, Hastings Professor of Preventive Medicine at the Keck School. “We have to maintain the same sort of level of effort to keep the levels of air pollution down. Just because we’ve succeeded now doesn’t mean that without continued effort we’re going to succeed in the future.”

Gilliland noted that the state’s historic drought is expected to raise particulate pollution.

Gauderman’s and Gilliland’s co-authors were Robert Urman, Edward Avol, Kiros Berhane, Rob McConnell, Edward Rappaport and Roger Chang, all from the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Keck School, and Fred Lurmann of Sonoma Technology Inc.

— Carl Marziali