A tiny bluish region deep in the brainstem has outsized impacts on how we learn and make memories in old age, according to a new study in Nature Human Behavior led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, Germany. USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology Professor Mara Mather, PhD, a coauthor of the new study who also is a professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, has studied the locus coeruleus — literally “blue spot” — and its important roles in attention, memory, and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease for several years.

What is the function of the locus coeruleus in a healthy brain?

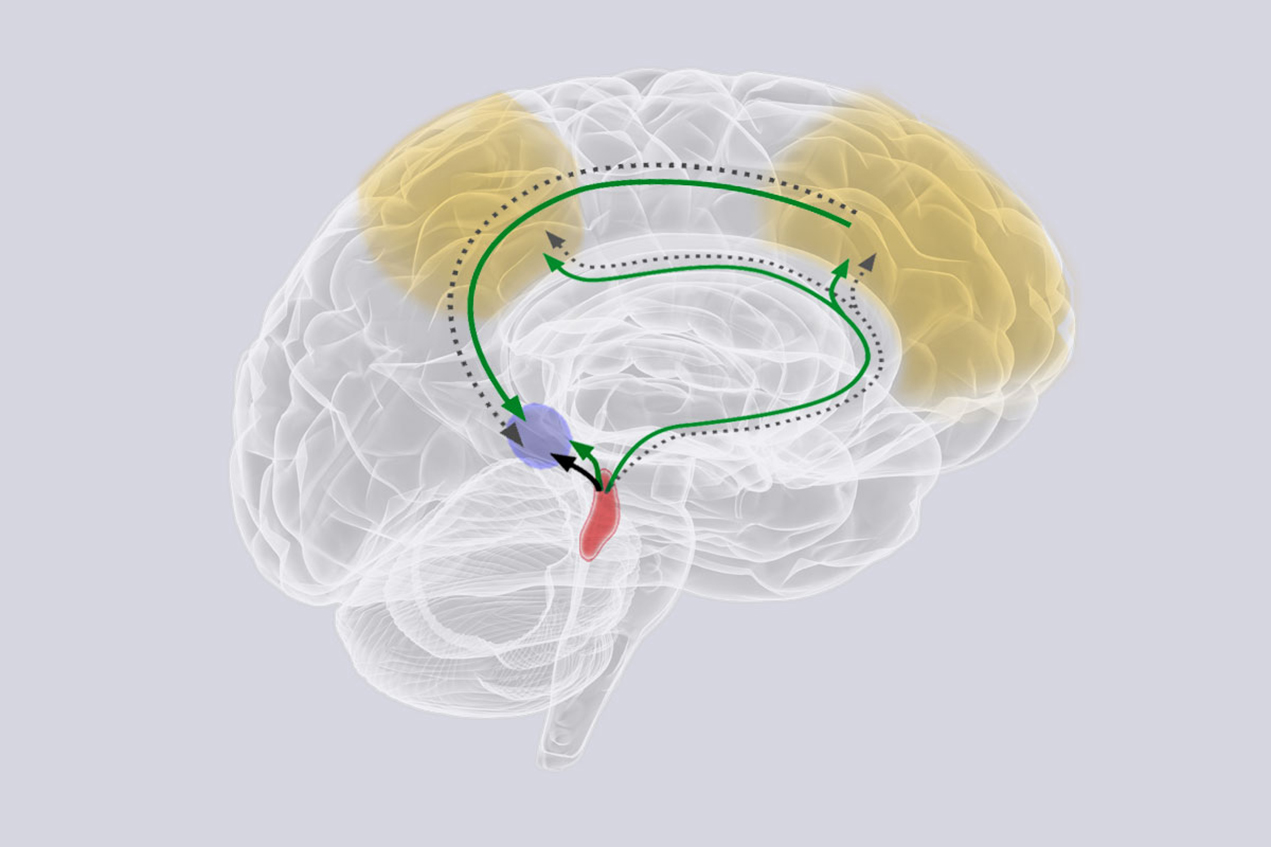

The locus coeruleus (LC) is a small part of the brainstem that is only 15 millimeters in size but is highly connected to the rest of the brain via an extensive network of neurons. The LC releases norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter responsible for regulating heart rate, attention, memory and cognition. Changes in LC activity appear to be responsible for how our memories are formed during stressful or exciting events – memories can be strengthened or impaired depending on what we are paying attention to before or during an emotionally arousing event due to a feedback loop involving the LC.

What happens to the locus coeruleus as we age?

The LC’s high interconnectedness to other parts of the brain and proximity to the blood-brain barrier may make it more susceptible to the effects of toxins and infections compared to other brain regions. We’ve seen disrupted connections between the LC and the brain’s frontoparietal network in older adults correlate with being more easily distracted by irrelevant information than younger people when experiencing stress or powerful emotions. The LC also the first brain region to show tau pathology, the slow-spreading tangles of protein that can later become telltale signs of Alzheimer’s, so it appears to be ground zero for the disease. Though not everyone will get Alzheimer’s, autopsy results indicate that most people have some initial indications of tau pathology in the locus coeruleus by early adulthood.

What does this newest study tell us about the aging locus coeruleus?

The current findings are among the first to show a link between cognitive function and the integrity of the locus coeruleus in living humans. New MRI techniques now allow us to visualize the locus coeruleus in living people non-invasively, and we were able to compare individuals of different ages and see which older adults had LCs that looked more like those of younger adults. The study participants also completed neuropsychological memory tests, and as expected, the younger people did better on average than the older subjects. However, the older adults with “younger-looking” LCs performed better than their peers on the tests.

What do these findings mean for researchers looking for ways to fight Alzheimer’s and improve brain aging?

If neuropathological changes are visible in the brain before any age-related memory or behavioral problems arise, it could mean that there is a window of time to slow the disease’s progression. And if we eventually find that other disease processes impact the aging of the locus coeruleus, it may shed light on new targets for the prevention of Alzheimer’s and other cognitive decline.

— Beth Newcomb