Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, which means many children have experienced a cancer illness or even death in their own family. At the same time, many minorities are underrepresented in the fields of cancer-related science, research, medicine and patient care that affects their own families, communities and individuals.

That’s why the National Cancer Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, began requiring that funded cancer centers, such as the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, create and teach programs geared toward students in the K-12 range about what cancer is, how it works, how it’s treated and what careers are possible, as part of a broader push for STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education in the United States.

“To get them into these fields, you have to give them the spark very early on,” said Martin Kast, a leading researcher and educator and a professor in molecular microbiology and immunology and in obstetrics and gynecology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Teaching schoolchildren, Kast said, is an entirely different endeavor than educating graduate students and medical professionals.

“Still, I immediately said yes when asked to create such a K-12 program,” he added, “because I have connections to an educational STEM platform that reaches thousands of students and that is managed by my daughter, Dieuwertje Kast.”

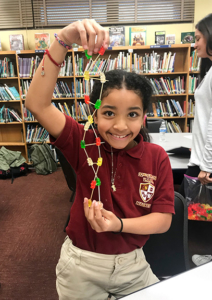

Jasiah Simpson, a Readersplus student at 32nd St. Elementary School, holds up a gummy bear DNA model during the genetics unit taught as part of the USC Wonderkids Program. (Photo/Courtesy of Dieuwertje Kast)

Dieuwertje “DJ” Kast is the STEM program manager for the Joint Educational Project (JEP) based at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. Recognized by Forbes magazine in its “Top 30 Under 30 in Science,” DJ Kast has a BS and MS in biology, a MA in science teaching, all from USC, and is pursuing an EdD at the USC Rossier School of Education, focusing on teacher education in multicultural societies and specifically in STEM.

The younger Kast manages two STEM programs at JEP: the Young Scientists Program and the Wonderkids curriculum. The latter introduces first- through third-grade students in the afterschool program to careers in STEM. Various science fields are covered in two-week blocks through literature and hands-on activities. The final lesson in each block is presented by guest speakers — professional scientists from each field of study — who share their work and to engage children in fun science activities so that they understand more about the field. Wonderkids beta-tested the curriculum for the first time in the spring.

“USC’s programs reach out to thousands of students around the main campus, and we are planning to extend the STEM and cancer education programs to the schools surrounding the Health Sciences Campus,” DJ Kast said. This gave her father an already effective platform to which a cancer curriculum could be added, rather than launched separately.

Explaining cancer to kids

Graduate student Anupam Singh, who studies molecular and computational biology, said the opportunity to design cancer education to a curriculum for students in grades K-3 provided an opportunity she had been seeking to give back to the community in which she now lives.

“Cancer is very scary, even to adults,” she said. “We thought about it: How do we teach cancer to kids? Will it scare them? Should we even talk science to them? We decided not to lie: Cancer does involve death, but not always.”

The curriculum designed by DJ Kast, Singh and the cancer education team turns learning cancer basics into play, using props and child-friendly games.

“Kids are having fun, but at the same time they’re learning science,” Singh said. “They learn that cancer is not like a cold you can catch. You can give someone with cancer a hug. Cancer is something that goes wrong inside your body, and it can be treated.”

The classes, which run after school in 90-minute sessions for about four hours per week over nine weeks, use games to show children at a very basic level what cancer is and how it’s treated. In one session, children reach into a box of small cold packs, all but one of which are soft and squishy. One has been frozen so that it’s hard, the way cancer often appears as something hard inside an otherwise healthy human body.

What’s in the box?

In another exercise, children are presented with a sealed box representing a human patient. Inside are plush toy cells with smiles on the outside, but some of which have been turned inside out to become menacing (but cute) cancer cells. To remove these from the box, students use a pair of grabbers. It’s a simple demonstration of how robotic cancer surgery works.

In yet another exercise, children build DNA double-helix models by using toothpicks to connect Gummy bears in four different colors representing the four amino acids. They then break open the helix by cracking one of the toothpicks, demonstrating how DNA strands can be corrupted to cause cancer.

DJ Kast said the program was begun at the earliest grades rather than high school, so that “we don’t lose those students as they move up.” In fact, the K-3 curriculum is meant to connect to existing programs for grades 4-5 and beyond.

A take-home lesson in explaining cancer to kids

The Wonderkids curriculum, which has hired four undergraduates so far to teach classes, also benefits from having the world-renowned Martin Kast available to visit class and talk about the rewarding life of a career in cancer research and treatment. His speaking engagement included giving students a take-home lesson for their parents: 8-year-olds are instructed to stick pins in a styrofoam ball to represent the human papillomavirus (HPV) responsible for an inordinate number of cervical cancer cases. They’re instructed to go home and show the virus model to parents, telling them that HPV can cause cancer as they get older, but it can be prevented at the recommended age of 9 to 12 with the name of the vaccine they’ve memorized: Gardasil.

Despite his reputation as a lecturer who educates undergraduate, graduate and medical students, Kast said, “For the first time in many, many years, I was nervous to go into a class — a class of first- to third-graders. I thought, what the heck am I going to tell these kids? But the connection was almost instantaneous. These kids are very engaged. They really want to learn.”

— Paul Boutin