Could microbes found on the International Space Station affect astronauts’ health in long-term space travel?

As NASA sharpens its focus on Mars, USC School of Pharmacy researchers are working with the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory to provide answers to that question.

NASA’s six-part “Microbial Tracking” investigation seeks to inventory and characterize microorganisms found in the air and on surfaces of the International Space Station. Astronauts on the station collect samples and send them back to Earth, allowing scientists to better understand how the stresses of microgravity and the enhanced radiation conditions in space affect the microbial flora on the International Space Station.

“NASA is trying to see whether we can go to Mars and beyond,” explained Jet Propulsion Laboratory senior research scientist Kasthuri “Venkat” Venkateswaran, PhD, principal investigator for the experiment. “In a closed environment, people have to inhale and exhale what they breathe. We need to know what we are dealing with, so we can come up with an appropriate countermeasure to mitigate problems. We need to know all of this because you don’t have 9-1-1 to call to get them back.”

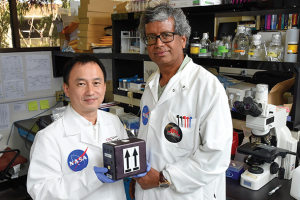

Clay Wang and Kasthuri “Venkat” Venkateswaran launched fungi into space to potentially develop new medicines for use both in space and on Earth. (Photo/Gus Ruelas)

Where humans go, microbes follow

USC has been involved in the project since 2015. Clay C. C. Wang, PhD, professor of pharmacology and pharmaceutical sciences and chemistry at the USC School of Pharmacy and the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, originally collaborated with Venkateswaran on the launch of Micro-10 and BRIC-NP, two first-of-their-kind research missions to study whether the effects of microgravity and enhanced radiation might influence fungi on the International Space Station to produce novel compounds.

That collaboration between JPL and the USC School of Pharmacy — with Wang and his team providing expertise on fungi and secondary metabolites — has evolved to include work on Microbial Tracking investigation.

Wang’s team at the USC School of Pharmacy, which includes doctoral candidate Adriana Blachowicz, a former graduate researcher at Venkateswaran’s lab, have been studying microorganisms sampled from the International Space Station’s air filter and a hard surface adjacent to the station’s Cupola window.

“Wherever there are humans, there are microbes,” Wang said. “We’re trying to understand the microbes in the International Space Station, and in doing so, possibly find new solutions that could support future long-term space travel.”

The team describes identifying two strains of Aspergillus fumigatus, a common airborne fungi that can cause life-threatening infections in individuals with weakened immune systems. The findings — that the Aspergillus fumigatus strains sampled from the International Space Station were actually more virulent than “control” strains found on Earth — were reported in a study published in mSphere on Oct. 27, and presented by Blachowicz at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society for Gravitational & Space Research in Cleveland on Oct. 27.

“Aspergillus fumigatus is an opportunistic pathogen that can affect the health of immunocompromised hosts, like astronauts,” said Blachowicz, a lead author in the study, who added that further research on samples taken directly from the station will help scientists gain an even better understanding of how to protect astronauts’ health in future long-term space travel.

NASA has already awarded the group a grant to continue the investigation.

Nancy Keller of the University of Wisconsin-Madison is also involved in the investigation. Benjamin P. Knox and Jonathan M. Palmer of the University of Wisconsin-Madison were other leading authors on the mSphere study and Jillian Romsdahl of the USC School of Pharmacy was a contributing author.

— Michele Keller