USC researchers have discovered a secret sauce in the brain’s vascular system that preserves the neurons needed to keep dementia and other diseases at bay.

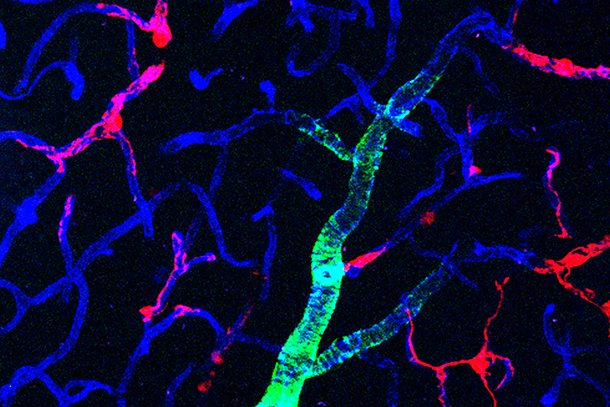

The finding, in a mouse model of the human brain, focuses on a specific cell called a pericyte and reveals that it plays previously unknown role in brain health. Pericytes secrete a substance that keeps neurons alive, even in the presence of leaky blood vessels that foul brain matter and result in cognitive decline.

The study, which appears June 24 in Nature Neuroscience, helps explain the cascade of problems that lead to neurodegeneration after stroke or traumatic brain injury, as well as in diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s — and suggests a potential strategy for therapy.

“What this paper shows is if you lose these vascular cells, you start losing neurons. The link with neurodegeneration was really not that clear before,” said senior author Berislav Zlokovic, MD, PhD, director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

The discovery comes at a time when scientists are beginning to understand Alzheimer’s disease as the result of multiple processes that begin long before memory loss sets in. Many researchers are shifting their focus from the amyloid plaques that accumulate in the brain later in life toward other targets earlier in the timeline.

Zlokovic, for example, studies the layers of cells that make up blood vessels in the brain. His previous research shows that the more permeable — or leaky — a person’s brain capillaries are, the more cognitive disability they have.

How these findings may help prevent Alzheimer’s

For this new experiment in mice, Zlokovic zeroed in on pericytes in the brain’s blood vessels. Pericytes help regulate blood flow and keep blood vessel walls sealed tight. When researchers artificially removed pericytes, they saw rapid degeneration of the blood-brain barrier, a slowdown of blood flow and the loss of brain cells.

To further understand their role, the scientists infused mice with a protein, or growth factor, secreted by pericytes in the brain and not found elsewhere in the body. They found that, even with pericyte cells artificially removed, the growth factor protected neurons and the brain cells didn’t die. The results persisted even with constricted blood flow.

Because these pericytes are implicated in many diseases — including Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, stroke, brain trauma and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis — the research offers intriguing possibilities for further investigation.

“This opens up an entirely new view of the possible pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease,” Zlokovic said.

In addition to Zlokovic, other authors — all from the Keck School of Medicine — include senior co-author Zhen Zhao; first co-authors Angeliki Nikolakopoulou, Axel Montagne, Kassandra Kisler and Zhonghua Dai; and Yaoming Wang, Mikko Huuskonen, Abhay Sagare, Divna Lazic, Melanie D. Sweeney, Pan Kong, Min Wang, Nelly Chuqui Owens, Erica Lawson and Xiaochun Xie.

The study was supported with grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG039452, R01NS100459, R01AG023084, R01NS090904 and R01NS034467) and the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence for the Study of Perivascular Spaces in Small Vessel Disease.

— Leigh Hopper