By Marie Rippen

Sweat is important — without it, we would overheat and die. In a recent paper in the journal Public Library of Science One (PLOS ONE), USC faculty member Krzysztof Kobielak, MD, PhD, and a team of researchers explored the ultimate origin of this sticky, stinky but vital substance — sweat gland stem cells.

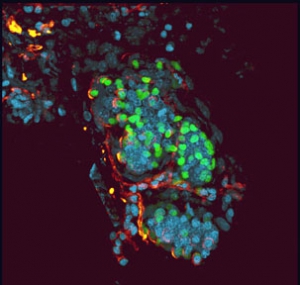

Kobielak and his team used a system to make all of the sweat gland cells in a mouse easy to spot: labeling them with green fluorescent protein (GFP), which is visible under ultraviolet light.

Staining of slow-cycling sweat gland cells (green) with the protein laminin (red) and the fluorescent stain DAPI (blue).

(Photo/Yvonne Leung)

Over time, the GFP became dimmer as it was diluted among dividing sweat gland cells. After four weeks, the only cells that remained fluorescent were the ones that did not divide or divided very slowly — a known property among stem cells of certain tissues, including the hair follicle and cornea. Therefore, these slow-dividing, fluorescent cells in the sweat gland’s coiled lower region were likely to be stem cells.

Then, the first author of this paper, graduate student Yvonne Leung, tested whether these fluorescent cells could do what stem cells do best — differentiate into multiple cell types. To the researchers’ surprise, these glowing cells generated not only sweat glands, but also hair follicles when placed in the skin of a mouse without GFP.

The researchers also determined that under certain conditions, the sweat gland stem cells could heal skin wounds and regenerate all layers of the epidermis.

“That was a big surprise for us that those very quiescent sweat gland stem cells maintain multi-lineage plasticity — participating not only in their own regeneration, but also in the regeneration of hair follicles and skin after injury,” said Kobielak, assistant professor of pathology at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

This offers exciting possibilities for developing future stem cell-based treatments for skin and sweat gland-related conditions, such as hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (excessive or insufficient sweating). It could also lay the foundation for creating fully functional skin — containing both sweat glands and hair follicles — for burn victims.

Additional co-authors on the study included: Eve Kandyba, PhD; Yi-Bu Chen, PhD; and Seth Ruffin, PhD, all from the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

The research study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R03-AR061028 and R01-AR061552).