Twice as many women as men develop Alzheimer’s disease, but even after years of research, aging experts are unsure why. Judy Pa, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, will lead a new big data study focused on the link between gender and Alzheimer’s risk.

“We believe there are distinct biological reasons for why women are at increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease — reasons that can be probed and discovered from data that already exist,” said Pa, who is based at the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute. “Previous research may have missed these gender-specific variations because the disparities can be subtle. This is why our targeted approach is important and necessary for addressing these questions.”

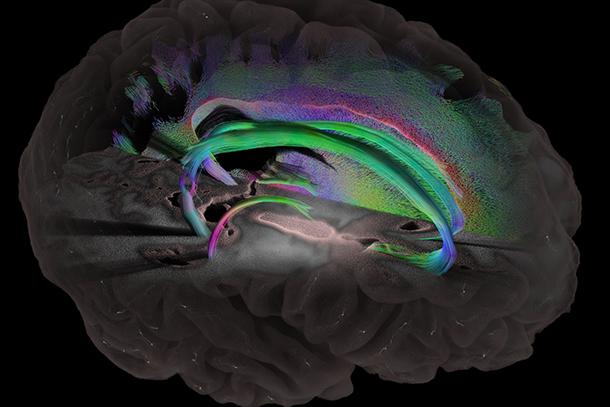

The five-year study is funded by a $3.78 million National Institutes of Health award and will use imaging and genetics data to explore the issue. Pa and her team include Alzheimer’s disease investigators across USC in the departments of Neurology, Psychology, Pharmaceutical Sciences and Preventive Medicine.

“Men and women may require specialized treatment strategies for a disease as complex as Alzheimer’s,” said Arthur W. Toga, PhD, Provost Professor of Ophthalmology, Neurology, Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, Radiology and Engineering; Ghada Irani Chair in Neuroscience; and director of the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute. “It’s important to understand these differences so we can develop effective targeted therapies.”

Theories abound as to why women face a higher Alzheimer’s risk than men. For decades, researchers assumed that longevity explained the disparity: women live longer than men, thus they are more often diagnosed. Recent data suggests longevity explains part of the difference, but isn’t the whole story.

Other potential explanations include hormone-related changes, differential stress-induced pathology and educational differences. For example, women experience a change in energy resources throughout the body after menopause, which may impact neurological processes, researchers said.

The study aims to aggregate clinical, cognitive, imaging, and genetics data from more than 3,000 people, combining multiple existing datasets with comprehensive data types.

“We’re leveraging existing resources,” Pa said. “The data are already there, they just need to be managed in specific ways. The tricky thing with big data is harmonizing it — many attributes will need to be cleaned up and reconciled between datasets. And most importantly, understanding the biological relevance of findings when using a big data approach is critical.”

— Zara Abrams