Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is participating in the first-ever clinical trial using stem cells from umbilical cord blood to delay or even prevent heart failure in children born with a rare congenital heart defect that leaves them with half a heart.

The Phase I study is part of a multi-center collaboration dedicated to employing innovative therapies to improve outcomes for children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a congenital heart defect in which the left ventricle is severely underdeveloped. The HLHS Consortium, launched at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota in 2017, involves four regional centers. CHLA, the only West Coast member, makes the initiative bicoastal.

“We’re proud to be part of this select group of institutions,” said Vaughn Starnes, MD, chair and Distinguished Professor of Surgery, H. Russell Smith Foundation Chair for Stem Cell and Cardiovascular Thoracic Research at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and co-director of the Heart Institute at CHLA. “As a leading center for medical and surgical treatments for HLHS, we want to be at the forefront of the next transformative therapy for treating this complex condition.”

In addition to the Mayo Clinic, other Consortium members include Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Minnesota Children’s Hospital.

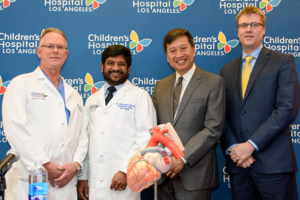

Vaughn Starnes, Ram Kumar Subramanyan and Pierre Wong, all of the Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, are seen with Timothy Nelson, director of the Mayo Clinic’s Todd and Karen Wanek Family Program for Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. (Photo/Children’s Hospital Los Angeles)

“It is very exciting that Children’s Hospital Los Angeles has joined the HLHS consortium. It means that individuals with HLHS now have more options when it comes to participating in groundbreaking clinical trials and other research,” said Timothy Nelson, MD, PhD, director of the Mayo Clinic’s Todd and Karen Wanek Family Program for Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome.

In HLHS, the left ventricle of the heart can’t pump oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the rest of the body. Without surgical intervention, HLHS is fatal. Children undergo a series of three surgeries in their first three years to make the right ventricle the heart’s main pumping chamber and improve blood flow.

This first-of-its-kind clinical trial combines pioneering surgical techniques with regenerative medicine. “This is one of the earliest efforts at harnessing the power of stem cell technology for the care of children with a serious cardiac disease,” said Ram Kumar Subramanyan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of surgery at the Keck School who is heading the HLHS study in CHLA’s Heart Institute.

CHLA first performed HLHS surgery in 1992. In the decades since, doctors have found that as children with HLHS reach adolescence, their reconstructed hearts are deteriorating. For some, that means heart failure and the need for a heart transplant. “We are looking for novel approaches to this vexing problem,” Starnes said.

At the time of delivery, newborns enrolled in the study will have their umbilical cord blood collected and sent to the Mayo Clinic, where the stem cells are removed. Within a few hours of birth, the baby arrives at CHLA and has the first HLHS surgery two to five days later.

The second open-heart surgery, the Glenn procedure, takes place at about 6 months of age, when the baby’s own stem cells are injected back into their heart. The hypothesis is that stem cells will stimulate the heart muscle to grow during the critical first year of life, when cardiac cells still have the ability to proliferate. At about 3 years of age, the child then has the third surgery, the Fontan procedure.

All children in the study will be followed long-term, as doctors look for signs that their hypothesis is working to produce a stronger heart for these at-risk children.

Together, the HLHS Consortium members hope to recruit about 20 children for the Phase I umbilical cord blood study. CHLA investigators already have enrolled several families.

Funding for CHLA’s participation in the Consortium has been provided in part by the Taglyan Family.

— Candace Pearson