When Gianluca Lazzi, PhD, started out as an electrical engineer, he was working on safety assessments of electromagnetic fields. Essentially, he wanted to find out how to prevent people from being overexposed to those fields and hurting themselves. Today, he actually exposes people to those same electromagnetic fields in order to heal them. But wait … this isn’t a story about a professor changing his perspective on a technology and reinventing himself in the process.

Lazzi, who holds a joint appointment as a Provost Professor of Ophthalmology and Electrical Engineering at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering and the Keck School of Medicine at USC, helps build eye implants that can bring back vision in people with retina degeneration.

He studies photoreceptors — the cells in your eyes that turn light into electrical pulses. These pulses, in turn, stimulate neurons, which turn that into information for the brain. When the photoreceptors stop working, they perceive light but no longer send along the information.

Quite literally, the lights are on, but nobody’s home. But wait … this also isn’t a story about a professor who developed some new piece of technology that’s going to change the world.

This is actually a story about triggers. And how the right ones, at the right time, can change everything.

Of course, everything said about Lazzi above is true. He did change his perspective on his research and applied what he knew about electrical pulses to improving how we understand the brain. And he did create entirely new pieces of technology that use those electrical pulses in implants to bring back people’s vision.

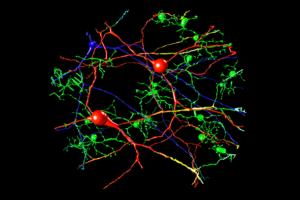

A ganglion cell network, when electrically stimulated with a new electrode array to increase the number of stimulation locations in the retina. (Image/Gianluca Lazzi)

Eye implants and stimuli

For our neural system to do anything, it needs a trigger — electrical stimulation. By activating the right cells through precise electrical stimulation, Lazzi’s implants can get those neurons in our eyes communicating with the brain again. The current itself is not actually healing the body, it’s simply the trigger that gets the many connected but different parts of the body to do what they’re supposed to together.

These tiny implants — only 5mm by 5mm in size — are not Lazzi’s alone but actually an ideal example of how great things can be done when people from different fields are brought together.

Stimulating the cells

It’s best to start at the beginning, before the implant is even built.

Our ability to capture and make sense of huge amounts of data has exploded in recent years. Through the use of computer technology and big data, scientists can now run the simulations needed to understand the complexity of systems like the retina or even the brain. Once the computer scientist builds and runs the simulation, Lazzi can stimulate the cells in the pattern the simulation created to see if the results are worthwhile.

If that checks out, production begins. Material scientists, mechanical engineers and electrical engineers fabricate and assemble the components to build a system that sends the correct signal, can be communicated with and be charged wirelessly — after all, no one wants to plug their eyeball into an electrical socket to charge their implant. Then a surgeon takes the device and physically implants it into the patient and tracks the results. All of these experts must be in close collaboration at all times to make sure the finished product does its job.

Finally, when everything else is finished, a writer is tasked with explaining it all.

A model of electrical stimulation of a sample of hippocampal tissue. (Image/Gianluca Lazzi)

A ‘beautiful, complicated circuit’

When it comes to this intersection of engineering and medicine, electrical engineers are often perfectly positioned to be the triggers.

“Our entire neural system can be interpreted as a beautiful, complicated circuit,” Lazzi said.

And no one understands circuits better than electrical engineers. Of course, it’s actually a two-way street. If medicine can learn more about the brain from engineers, so too can engineers learn more about circuitry from doctors. A good example is the age-old signal processing challenge of “noise.” Noise is unwanted or unknown information that shows up during the process of capturing a signal and interferes with the results. The more noise a test has, the less reliable it is.

One challenge Lazzi is working on is the spontaneous firing of ganglion cells in blind people.

“The cells don’t perceive light anymore, but they still randomly fire off from time to time, creating a kind of biological ‘noise,’ ” Lazzi said.

By understanding how noise works at the cellular level in the body, electrical engineers may develop new insights into how to build circuitry in the lab.

And the ramifications don’t stop there. In an attempt to create an eye implant that could receive data and charge wirelessly more effectively, Lazzi and his team began experimenting with liquid metal coils. They realized that this metal could be turned into extremely elastic fibers — a kind of stretchy conductor. The fibers are so small and flexible that they can be woven directly into clothing. It’s an advancement that can have a profound effect on the future of wearable technology such as respiration sensors or heated clothing, meaning that no one in Los Angeles will have to, uh, suffer through another winter again.

In 2017, Lazzi was named director of the Institute for Technology and Medical Systems Innovation at USC. The joint effort between USC Viterbi and the Keck School is charged with furthering this sort of collaboration between two of USC’s largest schools. With his years of experience as a collaborator and his electrical engineering background, you might say Lazzi is the perfect trigger for the initiative.

— Ben Paul