Without oxygen, cells can’t metabolize the energy necessary to maintain life. But a healthy level of oxygen within cells is key. Too little oxygen means not enough energy and too much means the cell can enter the death cycle prematurely. The work of the three 2018 Massry Prize laureates illuminated the process that works fundamentally to maintain this essential balance.

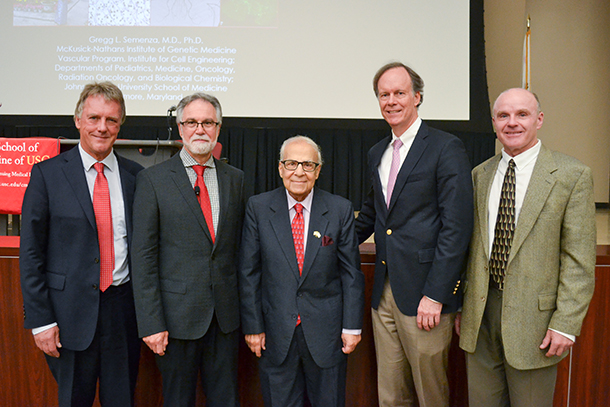

The scientists involved gave lectures on Sept. 20 on the Health Sciences Campus. The talks illustrated how their interlocking research pulled back the veil on a biological mystery and may lead to new treatments for fundamental human ailments including cardiovascular disease, anemia and cancer.

During his presentation Gregg L. Semenza, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, recalled the process of discovery of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) protein, which clings to DNA and prompts expression of the erythropoietin gene, which in turn is released by the kidney to increase red blood cell production. Semenza noted, “This is a beautiful, homeostatic system to ensure systematically that there’s adequate oxygen delivery.”

Next to speak was Sir Peter Ratcliffe, FMedSci, FRS, of Oxford University, the Francis Crick Institute London, and the Ludwig Institute of Cancer Research. Ratcliffe helped discover that HIF-1’s influence on the body extended far beyond the activation of genes responsible for red blood cell production. In fact, the protein is responsible for a range of responses that work to adapt to lowered oxygen levels, including blood vessel growth. Ratcliffe recalled thinking, “Darwinian evolution is fundamentally at odds with rational drug design. But might there be a drug anyway?”

The portrait of advancement was completed by William G. Kaelin Jr., MD, of Harvard Medical School, also an expert on a rare disorder called von-Hippel Lindau (VHL) disease, the effects of which include raised erythropoietin levels. Kaelin described how this clue led to the vital discovery that VHL proteins crucially react with HIF-1 when oxygen levels are high.

Kaelin jokes of the impulse that lead to his own research, “I was chief resident once, and chief residents love two things. They love rare, eponymous syndromes like von Hippel-Lindau disease … but we also like very intimidating differential diagnoses because if one knows one more cause of everything than anyone else, they’re the alpha dog on rounds.”

Thomas Buchanan, MD, vice dean for research at the Keck School, thanked all of the researchers involved for demonstrating that, “it wasn’t a linear path between an idea and a drug. You have to be persistent and you have to be able to take unexpected findings and turn them into some gold.”

The Meira and Shaul Massry Foundation, which promotes education and research in nephrology, physiology and related fields, established the Massry Prize in 1996 to recognize notable contributions to the advancement of health and the biomedical sciences. Fifteen Massry Prize recipients have gone on to win Nobel Prizes.

— Yancy Jack Berns